Honda’s first CL72 250 Scrambler was lashed to the bumper of many a Conestoga wagon as it made its way westward, and I’m pretty sure it was a Kawasaki KLX300 that I wheelied over backwards, circa 1997, that really dampened my enthusiasm for stunting. At least Honda’s had the decency to change its nomenclature over the years to give the impression of evolution. Kawasaki is standing pat with the 292 cc Single that’s powered its KLX since 1996, along with its KLX nomenclature.

2021 Honda CRF300L & Rally Review – First Ride

2021 Kawasaki KLX300 Review – First Ride

Sort of. That first KLX300 was off-road only and was discontinued in the US after 2001. KLX250 then appeared circa 2006 as a dual-sport, went in and out of production, re-emerged updated and fuel-injected in 2018 – which set the stage for the boring-out and re-introduction of a new KLX300 for 2021. It uses the same 78 x 61.2mm bore and stroke as the original ‘97 thumper and looks just like it too, from the outside at least. What’s old is new again.

The Honda actually has evolved a bit. CRF-wise, the first L may have been the 230 of 2008 (Honda’s first dual-sport in 17 years according to our test) followed by the CRF250L in 2013, which got upgraded to 300 status just last year via an 8mm-longer stroke taking the Honda single to 286 cc. Is there anything wrong with sticking with what works? I guess not. In fact there’s a lot right with it, I thought to myself as Ryan Adams and I pounded along through yet another rocky section of fire road on the way to Santiago Peak.

This pair of OG adventure bikes are all about short-range reconnaissance. Cheap to buy, maintain, and run, they’re built for exploring the world outside your back door.

| Honda CRF300L | |

|---|---|

+ Highs

|

– Sighs

|

| Kawasaki KLX300 | |

|---|---|

+ Highs

|

– Sighs

|

They’ve had plenty of time to work out all the bugs, of which there seem to be very few on either bike. Evolution has seen to it that these two value-packed dual-sport bikes have almost converged into one, just with different coloration, as they’ve both adapted to the same harsh conditions over the years. So much so that neither one of us can even be bothered to carry a flat kit. Riding these things, it feels like nothing could go wrong to spoil your fun; just try to avoid the sharpest rocks. How did I loop out a 22-hp bike 25-some years ago anyway?

You’re not going to confuse either of these bikes with something like a KTM 350 EXC, but for less than half the price of a bike like that, the little Honda and Kawi both buffer your behind with serious suspension travel – 10.2 inches at either end of the Honda, and 10.0 and 9.1 inches f/r on the Kawasaki. At the same time, seat heights that look high on the spec sheet aren’t so high in person. That’s because the springing is light enough that sitting on these uses up at least a third of that travel – especially the Honda – and that makes them great round-town runabouts as well as reasonably competent offroad bikes.

On the pavement

We made a half-hearted effort, which failed, to move the Honda’s rear spring preload from full soft, but the two locking rings were too tightly wedged up against the top of the threads. As she sits, full soft, the Honda rides a bit lower in the stern, using up probably half its 10.2-inch travel just cruising down the road.

That gives it a smidge more trail, and gives the rider confidence the CRF is going to run straight and true at top whack – right around 90 mph indicated; 80 to 85 is more its happy place on the freeway. Once you get used to the busyness of the little single (not to be confused with buzziness, of which there’s surprisingly little), there’s nothing wrong with using the CRF for short freeway hops or even longer ones, depending on whether you were hugged as a child or not: More stoic and frugal individuals will like the CRF the more they ride it. The seat’s not wide but it is reasonably cushy, helped along, again, by ten inches of suspension travel at both ends.

Ryan Adams agrees: The CRF300L floats around like an old Cadillac. On pavement and off-road the Honda’s 10 inches of suspension travel soaks up bumps before they ever make it to your backside. For casual riders, this makes the 300L an excellent choice for subdued cruising over whatever you point it at.

Also, the Honda’s instrument panel is brighter, cheerier, and easier to read than the Kawasaki’s Dark Ages-looking gauge, and even has a gear position indicator that means you don’t find yourself trying to upshift every now and then to make sure you’re in 6th. Also a fuel gauge; the Kawasaki only has a light.

On bikes with no frills, little things make a difference. The Honda’s interface (top) is nicer to look at and with more info.

Meanwhile on the Kawasaki, you’ve got the power to go as fast as the Honda, but upwards of 80 mph, especially over rain grooves, you don’t get quite the planted, stable feel of the Honda. Maybe it’s down to different tires – Dunlops for the Kawi, IRC for the Honda – but maybe also because the Kawasaki’s firmer rear spring has the stern riding higher and reducing trail just a smidge; the specs say rake, trail, and wheelbase between the two bikes are all nearly identical, but the Kawi is quicker on its feet changing directions.

The tape measure says both handlebars are just about 23 inches thumb to thumb, but you’re sitting taller on the Kawi; footpeg-to-seat on it’s about 22 inches, to the Honda’s 21, so you take a smidge more windblast, too. That also feeds the Kawasaki’s more flighty feel. And the whole time, the KLX motor just feels a bit more coarse than the less oversquare Honda single. Fixing that might be as simple as swapping on the tapered aluminum handlebar from the KLX accessories page.

RA: After riding both bikes on the freeway, it was surprising how different they felt at speed. The CRF300L cruises at 75 mph pretty happily at just under 8,000 rpm. The KLX300 will do it, and even make it all the way to 85, but it feels cruel to force it to do so. I saw a top speed of 90 mph on the Honda, but again, it’s pretty happy at 75 or anything below – and surprisingly smooth. The KLX felt best at about 55 or 60 mph. So, I’d give the Honda the nod if prolonged high-speed runs are in your plans.

All that just backs up what’s pretty obvious. Neither of these is an adventure bike meant for long highway miles. These are for day or half-day adventures that start at your back door while other people are golfing, and mostly encompass backroads and dirt ones. Having said that, I rode the KLX from Burbank to Orange County 60 miles through rush-hour LA traffic after I caught the Pacific Surfliner to Brasfield’s digs to pick the bike up, and it’s not a bad I-5 lane-splitter at all for the urban cheapskate. With a nice topbox or milk crate on the back seat or some soft saddlebags, these bikes are right behind a midsize scooter in terms of practicality. In fact, they deal with rough pavement way better than any scooter, and there’s way more rough on this LA course than groomed. Speaking of scooters, both these bikes have nice easy-to-reach helmet locks.

Brakes-it

Should some motorist cut you off or open a door in front of you while you’re slaloming through traffic, however, you’ll discover the weak point of both bikes: their brakes aren’t great. Tiny front discs and two-piston slide-type front calipers designed for dirt don’t pack much power or feel on pavement. Honda will sell you an ABS version of the CRF for $300 more, but you have to squeeze the front lever so hard to lock the front tire you almost don’t need it unless you ride in the damp a lot. Personally, I’d have the ABS option anyway.

Don’t even think about touching this when you’re riding downhill on ice you fool. The Kawi front disc is 250mm to the Honda’s 256, both squozen by old-timey two-piston calipers.

The Kawasaki’s front brake is a bit more powerful and feely, but the components are almost identical, so it might just be a brake pad thing. If Kawasaki offered an ABS version, I would’ve liked to have sampled it riding through an icy downhill section of our test mountain, but they don’t, and so I crashed. Two times, just to be sure, in two icy sections; yes, there is no ABS.

Let that be a lesson: Better to use the nice rear disc both bikes have in low-traction situations. The foot controls on both bikes are steel; it was easy to bend the Kawi’s lever back into almost-shape later with a big screwdriver. Also, the underbelly of the Kawi’s engine is protected by a small aluminum skidplate between the frame tubes. Not the Honda’s. We also both liked the Honda’s front pre-notched brake lever better when I accidentally made it into a “shortie.”

RA: Combined with the super cush fork on the CRF300L, the front brake is, at times, downright scary. Off-road, the lack of bite (and power in general) is manageable, but on road at speed, it made lane splitting all the more nerve-racking. The Kawasaki’s front brake offered pretty great feel on-road and off for a sub $6,000 motorcycle. Compared to the Honda, it is miles ahead in terms of power, too.

Most of the time, though, the brakes are gonna be perfectly adequate. In the dirt (or ice) you don’t want too strong a bite – and neither bike is much heavier than 300 pounds, so there’s not that much to decel. Little bikes like these, ridden in traffic, seem to sharpen your clairvoyant powers.

Offroad

When we first hit the bumpy, rocky stuff, I felt like both bikes had cheap, creaky suspension that was bouncing me around a lot. Soon enough, I learned it was the cartilage and soft tissue in my old joints, and as soon as that stuff came up to temperature, everything felt smoother and began to come together.

The KLX rear shock is a higher quality unit with a piggyback reservoir and rebound-damping adjustment; its performance compared to the CRF shock means the whole motorcycle handles more accurately and securely when you start upping the pace through the bumps: If you’re an aspiring offroad racer, your choice is already made. Then again, swapping a better shock under the Honda would likely have it running right with the Kawi if you could find something that fits. Or making a greater effort to twist its preload adjuster; there’s about an inch of virgin threads down there waiting for you to raise the rear end, and both suspensions are linkage types.

How much difference does swingarm pivot height make when dealing with 22 horsepower? I couldn’t tell you.

Ryan A: Overall the Kawasaki KLX300 feels like the better choice for those focused primarily on riding off-road. Its suspension feels better damped with much better bottoming resistance at both ends.

RA getting some sick air on the CRF. The Kawasaki lands better, with its compression- adjustable fork and rebound-adjustable piggyback-reservoir rear shock.

If you’re not an aspiring offroad racer but more an offroad explorer/adventurer, there’s not a lot in it between the two. The Honda’s lack of chops through the rough stuff really doesn’t bother me that much, because rather than bombing through, I slow down when I see the rough stuff coming. The CRF gives me the excuse I need. You can blast through on the CRF, but if you do it’s prone to bottoming out quicker, especially in the rear, than the KLX. But why not have a seat and pick smoother lines at a more sedate pace. Ahhhh… then again I’m like 180 lbs, lately, before I even gear up.

Ergo…

Beyond the KLX riding a bit higher in the rear, with an inch more seat-to-peg distance, and therefore being a bit harder to climb onto, both bikes feel pretty interchangeable to me, including their seats.

But Ryan, who’s 5’8 like me, but with a fresher ganglion network, says: the Honda’s ergos feel spot on, whereas on the Kawasaki, I would want to play with some different risers and bars to find my happy place. I also felt the Honda would probably work better for larger riders as the entire cockpit feels more open.

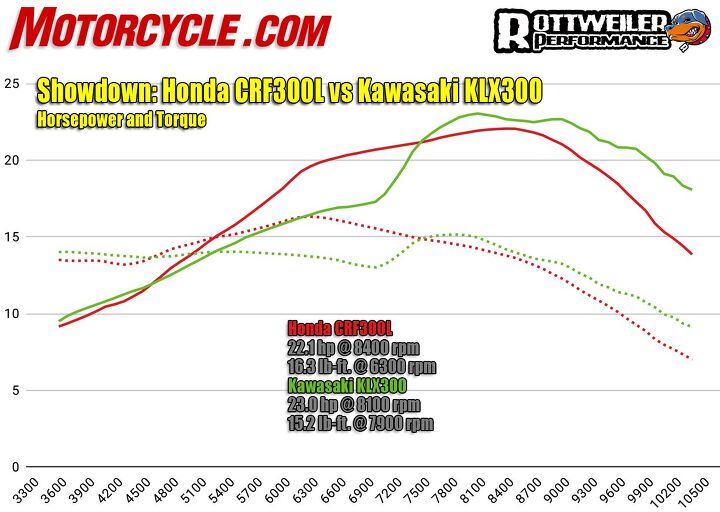

Massive Horsepower

Ahhhhhh, no. The Honda does have a slight bump in the midrange that Chris the dyno operator said he could feel, but I sure couldn’t in actual use – a whole 1.1-lb-ft more torque at just 6300 rpm.

It’s weird that the Kawasaki couldn’t use its 0.9-hp advantage to register a higher top speed or at least keep up? In any case, 22ish horses and 15 lb-ft is more than enough to completely entertain yourself and climb reasonable hills, if not mountains. When it comes to quality of power rather than quantity, though, the Honda’s more modern liquid-cooled double-overhead cam Single just feels a bit more, ahh, modern. It runs smoother in general, and feels like it’s just not working as hard as the Kawasaki’s older, more oversquare design most of the time. Again, the CRF gearbox shuffles its six gear pairs a tad more smoothly, and its clutch lever is a smidge lighter.

For being only 286 (Honda) and 292 cc, both little engines are surprisingly torquey and require less gear shifting than you might think to maintain forward progress: 2nd, 3rd, and 4th got us up Saddleback Mountain lickety-split without a lot of drama, and once you’re in top gear on the road, there’s not a lot of downshifting required to mesh smoothly with traffic.

Ryan A says: Off-road both bikes had enough grunt to stay out of first gear for the most part, though the Honda blows through first quickly, while the Kawi’s gears feel more evenly placed.

That’s all down to wet weights of just 306 for the Honda and 301 pounds for the Kawasaki. Both are positively waif-like between your thighs, and that frees your mind to attempt feats on these you wouldn’t on even a small adventure bike. Okay, I wouldn’t. KTM says its 390 Adventure weighs 348 lbs dry, so it’s probably more like 25% heavier than these dual-sports gassed up. The CRF and KLX confidently go and bounce off places on their 21-/18-inch knobbies that even the baby KTM, on its 19-/17-in. wheels, wouldn’t dare. A’course, if you’ve got $12k to spend, KTM’s 350 EXC-F dual-sport claims a dry weight around 230 lbs.

Wait for it…

For most of us with bills to pay, though, you really can’t go wrong with either of these highly evolved Japanese dual-sports. It’s another one of those where the best horse depends on the course. Make mine red! because I like the Honda’s overall luxurious (for a dirtbike) ride, its smooth-running little motor, and its better highway performance.

Ryan Adams had to go the other way of course: After riding the Big Bear Dual-Sport Run on the KLX300, I can attest to the amount of abuse the Kawi is more than capable of taking while dishing out loads of fun along the way. The low seat height, solid 292cc Single, and fully adequate suspension made for a great day of riding with friends in the mountains. Between these two, since my focus would be on off-road riding, it’s gonna be the KLX300 for me, dawg.

Both of these have been around as long as the crocodile for very good reasons. They’re cheap to acquire, easy to maintain, possibly impossible to kill, and a great way to bust out for some nature time without having to burn up your vacation days. Why not get both? They’re small.

| Scorecard | 2021 Honda CRF300L |

2021 Kawasaki KLX300 |

|---|---|---|

| Price | 100% | 93.8% |

| Weight | 98.4% | 100% |

| lb/hp | 94.9% | 100% |

| lb/lb-ft | 100% | 95.0% |

| Total Objective Scores | 98.6% | 97.1% |

| Engine | 87.5% | 85.0% |

| Transmission/Clutch | 87.5% | 80.0% |

| Handling | 72.5% | 80.0% |

| Brakes | 65.0% | 80.0% |

| Suspension | 70.0% | 80.0% |

| Technologies | 71.3% | 70.0% |

| Instruments | 77.5% | 65.0% |

| Ergonomics/Comfort | 80.0% | 67.5% |

| Quality, Fit & Finish | 80.0% | 77.5% |

| Cool Factor | 82.5% | 81.3% |

| Grin Factor | 80.0% | 82.5% |

| John’s Subjective Scores | 80.4% | 77.7% |

| Ryan’s Subjective Scores | 76.5% | 77.9% |

| Overall Score | 82.5% | 81.7% |

| Specifications | 2021 Honda CRF300L |

2021 Kawasaki KLX300 |

|---|---|---|

| MSRP | $5,249 | $5,599 – 5,799 (Camo) |

| Engine Type | Liquid-cooled single cylinder DOHC, 4 valves | Liquid-cooled single cylinder, DOHC, 4 valves |

| Displacement | 286 cc | 292 cc |

| Bore x Stroke | 76.0mm x 63.0mm | 78mm x 61.2mm |

| Compression Ratio | 10.7:1 | 11.1:1 |

| Max Power (dyno) | 22.1 hp @ 8,400 rpm | 23.0 hp @ 8,100 rpm |

| Max Torque (dyno) | 16.3 lb-ft @ 6,300 rpm | 15.2 lb-ft @ 7,900 rpm |

| Starter | Electric starter | Electric starter |

| Oil Capacity | 0.5 gallons | 0.35 gallons |

| Fuel System | PGM-FI electronic fuel injection | DFI with 34mm Keihin throttle body |

| Fuel Capacity | 2.1 gallons | 2.0 gallons |

| Tested Fuel Economy | 60 mpg | 56 mpg |

| Battery Capacity | 12V-7AH | 12V-6AH |

| Clutch Type | Wet multiplate, assist/slipper clutch | Return shift with wet multi-disc manual clutch |

| Transmission Type | 6-speed | 6-speed |

| Final Drive | Chain | Chain |

| Frame | Steel semi-double cradle | Steel semi-double cradle |

| Front Suspension | 43mm telescopic inverted fork. 10.2 inches of travel | 43mm inverted cartridge fork with adjustable compression damping. 10.0 inches of travel |

| Rear Suspension | Pro-Link single shock. 10.2 inches of travel | Uni-Trak gas-charged shock with piggyback reservoir with adjustable rebound damping and spring preload. 9.1 inches of travel |

| Front Brake | 256mm x 3.5mm disc with two piston caliper | 250mm petal disc with a dual-piston caliper |

| Rear Brake | 220mm x 4.5mm disc with single piston caliper | 240mm petal disc with single-piston caliper |

| ABS | Available, but not on as-tested model | N/A |

| Front Wheel | Aluminum spoke | 3.0″ x 21″ wire spoke |

| Rear Wheel | Aluminum spoke | 4.6″ x 18″ wire spoke |

| Front Tire | IRC GP-21F 80/100-21M/C 51P | Dunlop D605 3.00-21 51P |

| Rear Tire | IRC GP-22R 120/80-18M/C 62P | Dunlop D605 4.60-18 63P |

| Instruments | LCD | LCD |

| Length | 87.8 inches | 86.4 inches |

| Width | 32.3 inches | 32.3 inches |

| Height | 47.2 inches | 47.1 inches |

| Wheelbase | 57.3 inches | 56.7 inches |

| Rake x Trail | 27.5°/4.3 inches | 26.7°/4.2 inches |

| Seat Height | 34.6 inches | 35.2 inches |

| Ground Clearance | 11.2 inches | 10.8 inches |

| Curb Weight | 306 pounds (measured) | 301 pounds (measured) |

| Service Intervals | 16,000 miles | 12,000 miles |

| Colors | Red | Lime Green, Fragment Camo Gray |

We are committed to finding, researching, and recommending the best products. We earn commissions from purchases you make using the retail links in our product reviews. Learn more about how this works.

Become a Motorcycle.com insider. Get the latest motorcycle news first by subscribing to our newsletter here.